One of the greatest gifts of being a grandmother is the chance to share my own childhood memories and experiences with my grandkids, Molly and Declan. Usually, they feign interest, Sometimes they are honest. A few years ago, we watched, or tried to watch, the original Hayley Mills version of The Parent Trap together, Molly asked about twenty minutes in, “Is this almost over?” I squelched my urge to scream, “Are you kidding? This is iconic!” Instead, I calmly reached over to the remote and switched off the tv and VCR. “Wanna make some popcorn?” I asked. They were in the kitchen before I was off the couch. We ate our greasy, buttery popcorn sans Hayley. I learned my lesson.

The moment stuck with me as an unadulterated grandparenting failure. As the kids got older, I learned to be judicious in my choice of how to engage them. Ten-year-old Declan and I play the piano so we graze through my sheet music for a Disney duet to practice together. We also share a bizarre attraction to Snapchat and create videos using voice-changing filters while singing Aerosmith’s Dream On or Phil Collins’ Against All Odds. Molly, now twelve, likes to cook and bake. We scroll through our phones together and find recipes to try. Then we watch YouTube clips of The Office outtakes. They seek a different kind of engagement and I must evolve with their interests and access to technology.

I have found other ways to breach Molly’s sphere of interest. In addition to her culinary pursuits, she also enjoys acting and going to the theater. An appropriate birthday or Christmas gift for her can always be found in the listings for Broadway in Boston and other local venues for smaller-scale productions. For her twelfth birthday, I suggested tickets to Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella at the Northshore Music Theater. She was thrilled.

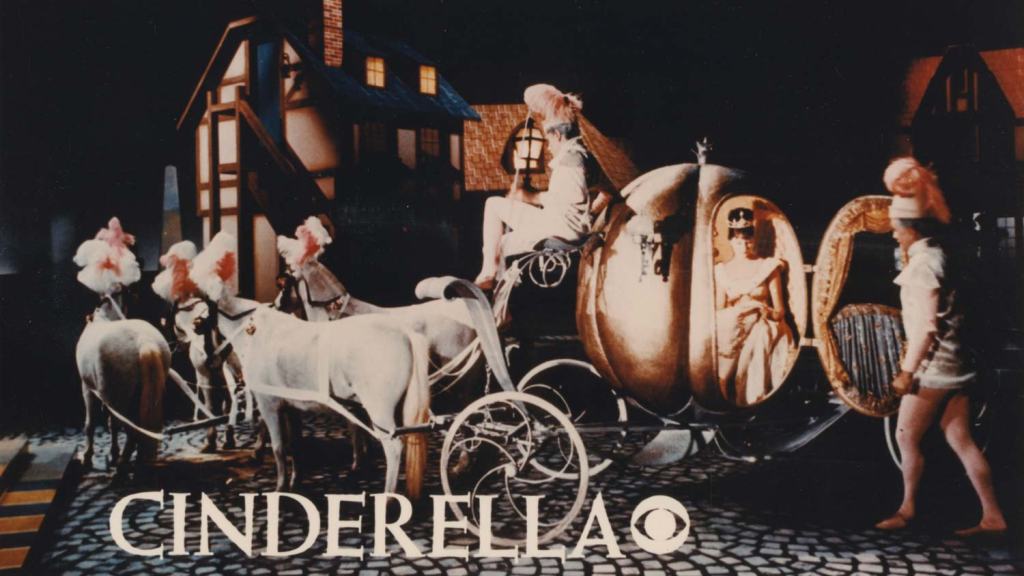

Although it was a gift for Molly, I selfishly chose the play based on my own childhood experiences. Once a year, long before tv viewing was ‘on demand,’ the CBS network aired the teleplay featuring Leslie Ann Warren as “Cinderella” and Stuart Damon of General Hospital fame as “The Prince.” The annual television event was so beloved by my generation, I believe watching Cinderella every year during our youth might have been as formative as the moon landing or the assassination of JFK.

The songs imprinted on my memory so well way back then that I still can recall the lyrics verbatim. On the night of the play, I started singing on the half-hour ride to the theatre and I appreciated Molly’s tolerance of my performance since I am a notoriously horrid singer. It’s been five weeks since the show and I haven’t stopped singing yet. It was “A Lovely Night” and it feels more like “Ten Minutes Ago” than over a month ago. (See what I did there? I incorporated the songs into my essay. Clever, huh?)

A few days after our outing, good-natured Molly agreed to watch the Warren/Damon Cinderella via 2022 ‘on demand’ magic. We dissected the sets and considered variations between the two productions we had seen. Unlike The Parent Trap, she didn’t seem bothered by the primitive presentation, which even I have to admit seemed pared down and basic. I don’t remember it being so static. I still loved every minute.

After seeing the play and rewatching the teleplay, I unintentionally dedicated the remainder of the summer to immersing myself in all things Cinderella. I downloaded the piano sheet music, which I practice every evening. I watched clips from the teleplay on YouTube while cooking dinner. Yes, I became a little obsessed but there was something pure and rejuvenating about reliving those special memories. As a bonus, by sharing those experiences with a grandchild, I bridged the time between my childhood and hers. I never imagined how gratifying that connection could be.

Summer is nearly over but I hope my Cinderella hangover will continue well into fall. In any case, I already know the next frontier in my quest to bridge generations: a viewing of The Trouble With Angels, the 1966 film about wayward girls in a Catholic boarding school. I’m not ready to give up on my girl Hayley and the chance for her body of work to be appreciated. I’ll have the popcorn at the ready, just in case.